The UK Media is making too many mistakes when reporting the climate crisis

The climate crisis is a threat that looms over the day-to-day life of most people and is a problem that will ultimately affect everyone. For most people, the way they learn more about this issue is through the mainstream media and general news that they consume. Because of this, it is of vital importance that the way in which the climate is reported by the media is examined and scrutinized to ensure that it is helping with climate progress and not hindering it. One way of examining climate reporting is to take a look at a large sample size of recent articles from publications across the political spectrum and analyse the strengths and weaknesses of this reporting. Matthew Pye, founder of the Climate Academy, believes that when looking at the state of climate reporting “it is really glitchy because they make some common mistakes”.

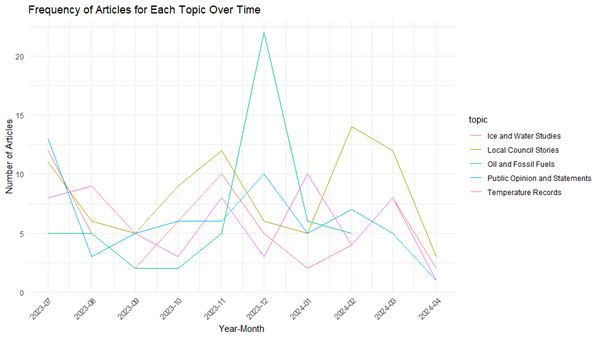

By examining the topics that climate-related articles focus on, we can begin to see trends in the coverage of the climate crisis. Out of over 900 BBC climate articles, 98 were local stories, meaning that they had a regional or council-level focus, as opposed to a bigger-picture view.

Josh Gabbatis from Carbon Brief, a site that covers the latest developments in climate science, said “It definitely makes sense that oil and gas discussions spiked during COP28 as the idea of a "fossil fuel phaseout" was a major topic at the conference. I'm not sure if that would necessarily be the case at every COP, although there is certainly more coverage of climate issues during the COP every year.” Whilst this is a natural part of the news cycle, it is important for climate change journalism to do more than just react to current events.

At a conference in 2023, Inga Thordar, the chief impact officer at Skating Panda, said “I think that there might be a tendency for journalism to cover the symptoms of the climate crisis instead of its causes.” This often comes from the reactive nature of the news cycle, articles are written in response to the individual events that Pye spoke about, rather than taking a systemic and holistic view of the entire crisis. To remedy this, some news organisations have provided more climate-related features or explainers. When this was discussed at the conference, however, there was a general sentiment that many news outlets need to go further in providing basic climate information in their explainers.

Furthermore, Pye believes that frequently people are speaking about climate in the wrong way. If someone were to talk about a ‘green small plant’, it just sounds wrong because the complex rules of the English language mean that a ‘small green plant’ is the correct thing to say. In the same way, the order of discussion points in the context of the climate crisis is important. Pye believes that frequently the first response to discussions of climate are expense and job security, but “this doesn’t take into account the fact that with a broken ecosystem nothing is possible”.

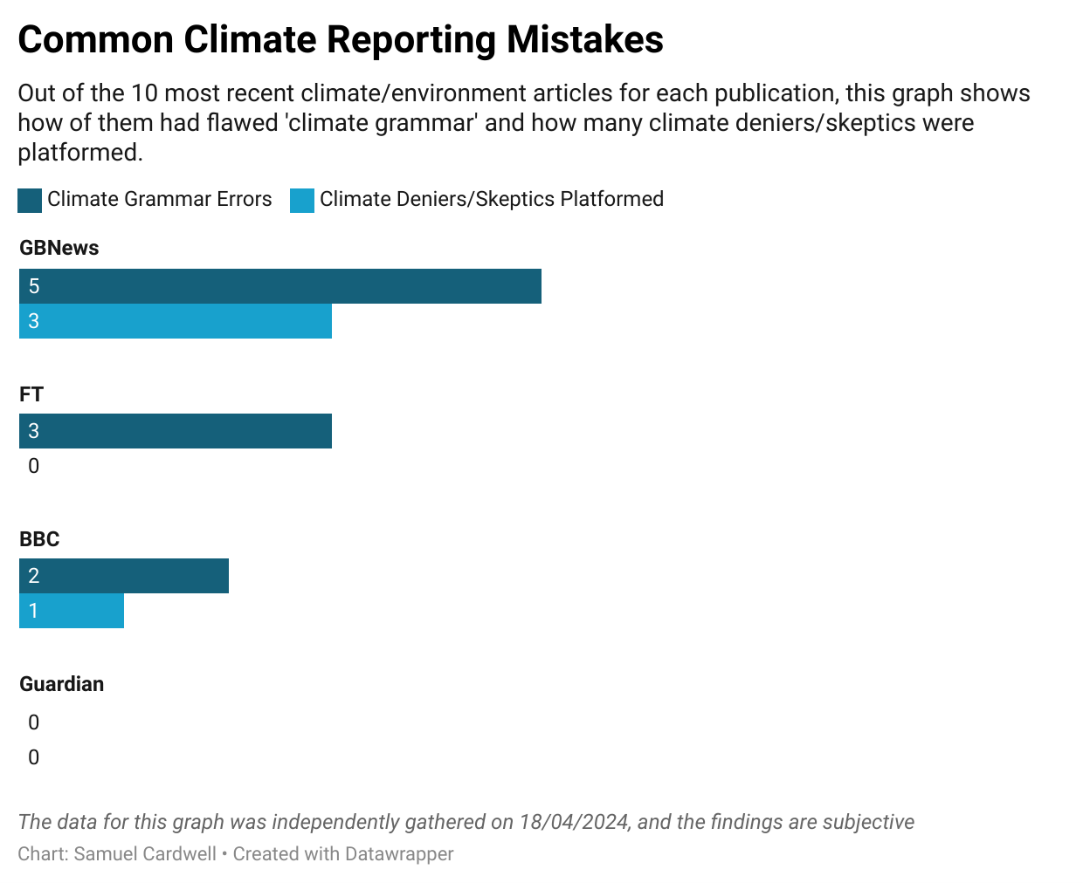

To investigate this issue, the 10 most recent climate articles from several publications were examined to search for the ‘incorrect’ usage of climate grammar.

To illustrate this point in practice. It is worth looking at some of the contents of the articles that were examined.

At one of the Newsrewired conferences, Gloria Dickie, a climate and Environment Correspondent at Reuters, said “There's a short-term outlook where people feel they are more inconvenienced by having to wait in traffic than the effects of the climate outlook. We can probably do a better job there.”

When looking at these articles, it was also highlighted that climate deniers and sceptics are still being platformed by some outlets. Historically, there has been a debate on this issue as to whether the requirement for neutrality means that all views should be represented in an article. However, many climate activists argue that this is causing harm to the climate movement. By presenting these views, publications are suggesting their legitimacy when it is scientifically proven that the climate crisis exists, is caused by humans and that action needs to be taken to mitigate the impacts of it.

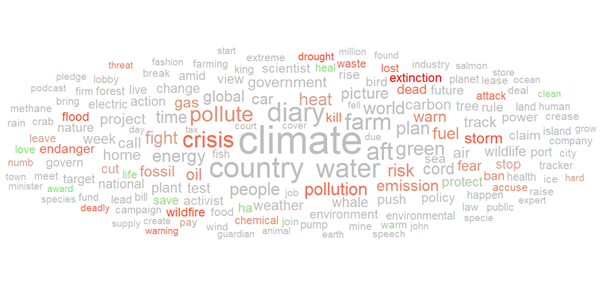

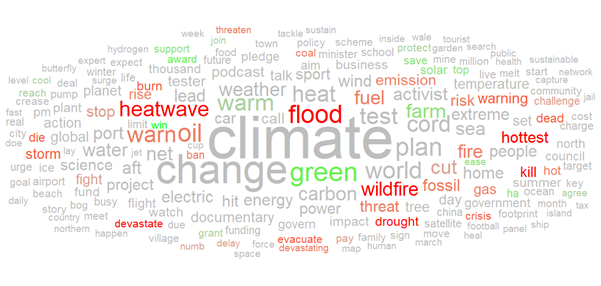

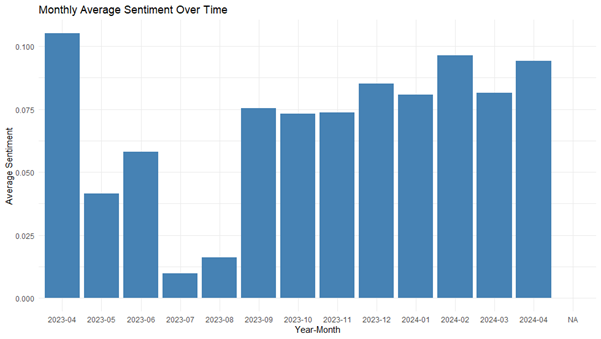

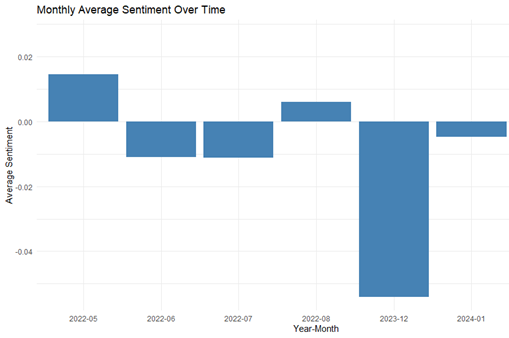

Another factor that is important to consider when reporting on the climate is tone. Solutions-based climate reporting has been argued to be more effective as it provides some level of optimism and hope for the reader, preventing the trap of despair and resulting in many people giving up. At the same time, a tone that is too positive can sugarcoat the harsh reality of the climate crisis and undermine the purposes of the reporting. By analysing the headlines of the BBC and Guardian the most common words and whether they are positive or negative can be identified, giving a general idea of the reporting style.

When presented with these findings, Josh Gabbatis from Carbon Brief said: “The issue with tone is that it depends on what exactly is being discussed. For example, a Daily Mail headline might mention climate in a negative way, but it is saying we shouldn't worry about climate change – while a negative Guardian article might mean we should worry more about climate change.” With this in mind, the key point is that these publications must be aware of the tone they take when discussing climate, with intentional guidance on what can and cannot be said.

One example of this is the Guardian’s transition to referring to the ‘climate crisis’ as opposed to ‘climate change’. Alongside this, climate ‘sceptics’ are now referred to as ‘deniers’ and global ‘heating’ instead of ‘warming’. This is reflected in the data, as heat was a more common word occurrence than warm for the Guardian. However, for the BBC both heat and warm had a similar amount of uses, suggesting that they should implement a policy to standardise the language being used.

When discussing this, Gabbatis also highlighted the fact that “One thing that immediately springs to mind is that the negative framing in the Guardian is presumably the newspaper saying ‘climate change is a disaster’ or something like that... whereas the BBC naturally maintains a more level tone.” Whilst this is often true, on average the monthly tone output by the BBC is more positive than not, whereas the Guardian fluctuates between positive and negative tones.

Whereas before it was noticed how the topics discussed changed during COP28, which is almost inevitable, it is interesting to note how much the tone changed. Not only does this demonstrate how climate reporting changes during events such as COP, but it also suggests that these events cause more negativity about the climate than positivity, which is arguably the opposite of their intentions.

From all this, it is clear that there are trends in the way that the mainstream media represents the climate crisis. It is a surprisingly common occurrence for articles to speak about job security or aesthetics of a local area before considering the damages and impact of climate change and across the board there seems to be a focus on local, reactionary storytelling. This is never more evident than when observing how reporting changes in response to big events such as COP28. Climate reporting is a key part of helping to mitigate the harms of the climate crisis, so it is incredibly important that the reporting is scrutinised and held to a high standard. Unfortunately, the UK’s coverage of the climate crisis is currently making too many mistakes too often.

Post a comment