How data is helping to understand the terrible harms of artificial intelligence

Artificial Intelligence is continuously poking its head into many headlines and industries across the globe. At the same time, for many people it is unclear what exactly AI is. It is often unclear what impact AI is currently having, who is most affected and what harms are being caused. Luckily, looking at some of the data surrounding AI can help to answer these questions and understand its impact.

For example, the OECD AI Incident Monitor (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development is a tool which shows how there 570 AI incidents happening across the world every single month. This marks a 30 per cent increase in reported AI incidents since the start of 2023.

Another dataset, the AIAAIC Repository (AI, Algorithmic, and Automation Incidents and Controversies), records detailed information about each incident they encounter and openly shares it for everyone to see. This is described as ‘a project which seeks to support the case for greater transparency and openness of AI and algorithmic systems by tracking and documenting AI related incidents’. This allows researchers and reporters to understand the extent of the harms caused by AI and how they are currently impacting the world.

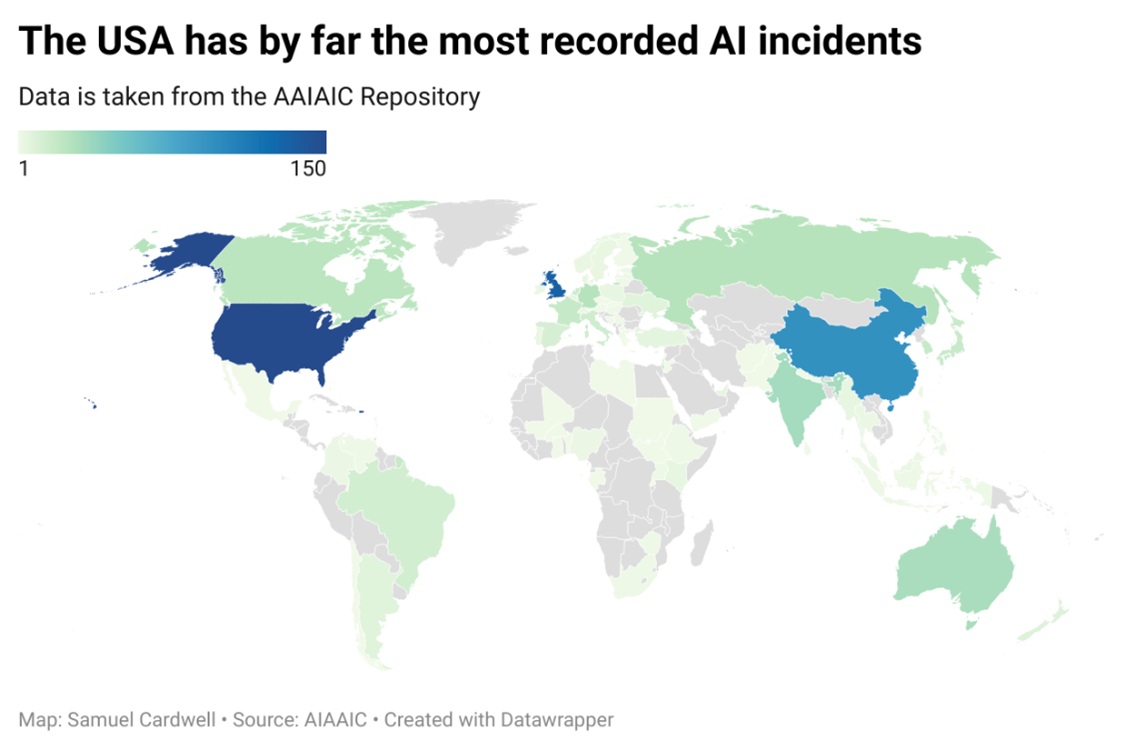

When considering the harms caused by AI, it is important to note that it does not affect everywhere equally. Charlie Pownall, the founder of the AIAAIC Repository, said “Some countries are more exposed to AI and its downstream impacts than others”. This is a result of many factors including the state of the economy, political systems, technological advancements in the countries and much more. At the same time, Charlie advised that “the repository is mostly western-focused and reflects the biases of its contributors”.

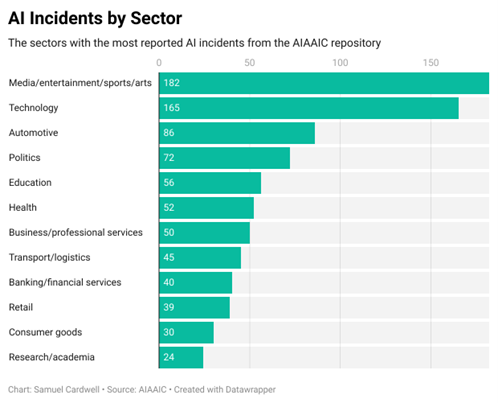

In the same way that the harms caused by AI can vary geographically, they also impact different sectors in different ways. One of the most impacted sectors is politics, where deepfakes have frequently been at the centre of political disinformation. One extreme example of this happened in 2019, where a video of Gabon’s president making a speech was supposed to be a deepfake that was being used to cover up the president’s illness. In one article, a deepfake expert, Aviv Ovadya, explained that the fact that deepfake technology is prominent enough to cast doubt is problematic, whether the presidential video was real or not. Since then, there have been debunked audio deepfakes of Keir Starmer harassing an aide and more recently Joe Biden telling people not to vote. The potential of AI to cause and increase political disinformation is one of its more sinister harms.

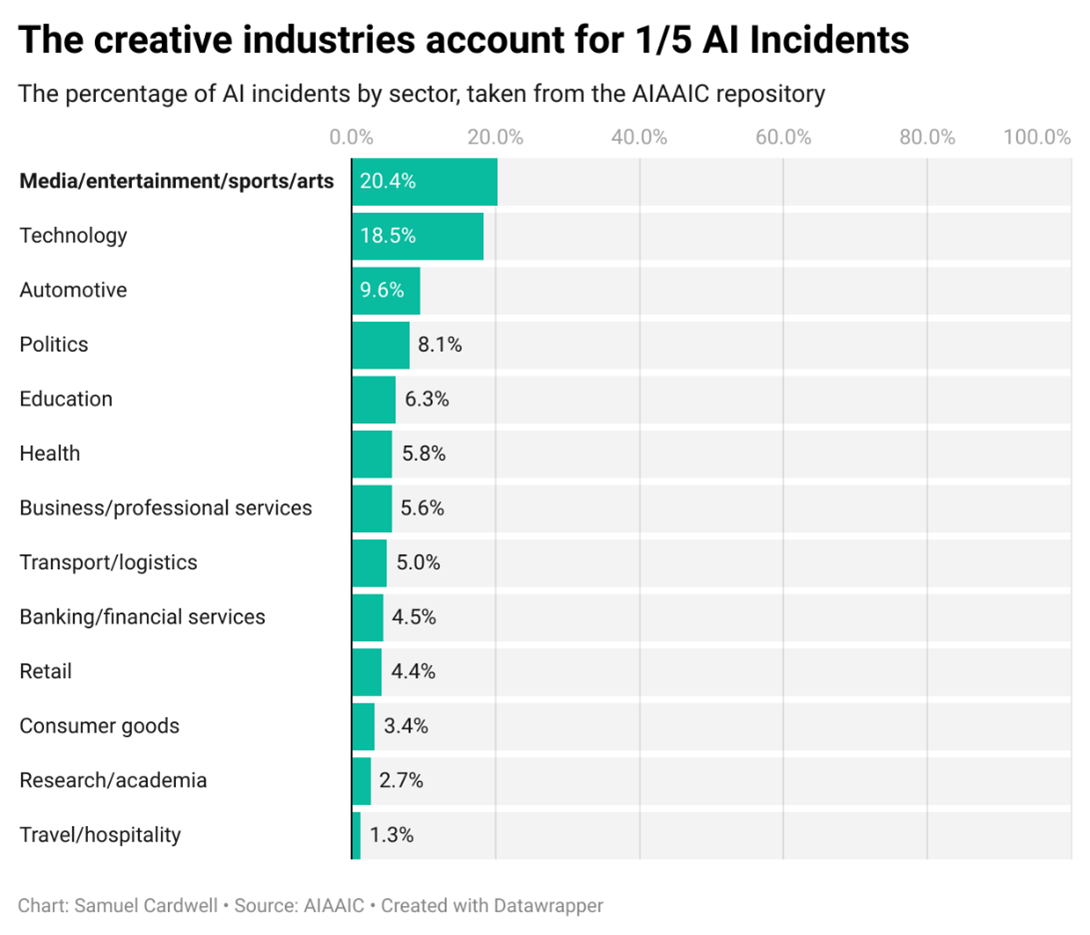

Currently, a lot of AI systems are being deployed in the creative industries, with over 20 per cent of incidents in the database coming from the media, entertainment, sports or arts industries. This is largely due to the success of chat bots and image generation sites such as Open AI’s ChatGPT and Dall-E 2, which lend themselves to creative enterprises.

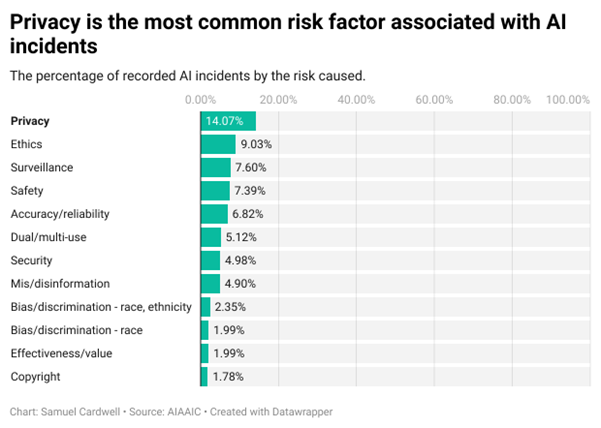

One of the fundamental issues in this area is plagiarism of other’s work, as the databases that feed these AI systems are currently built upon copyrighted content. This can lead to obvious copyright violations which can be generated from generic prompts and smaller artists who are concerned about losing income. However, copyright issues are one of the less frequent risks recorded in the AIAAIC. Issues such as privacy, ethics and surveillance are much more common.

This comes back to the mission statement of the AIAAIC, to “support the case for greater transparency and openness of AI and algorithmic systems”. This can only be achieved through a greater understanding of the harms AI is causing and an careful analysis of these incidents.

It is also important to consider that not all harm that is related to the use of AI happens after its deployment and so cannot be tracked through the AIAAIC dataset. One example of this is ‘ghost workers’. A lot of technology that uses AI is only possible through the processing of huge amounts of data. This data needs to be labelled by humans to allow it to be useful and this is done by ‘ghost workers’. These are people who work in remote across the globe, often done by the economically vulnerable and sometimes even prisoners. A report by Google’s deepmind described this situation as establishing “a form of knowledge and labour extraction, paid at very low rates, and with little consideration for working conditions, support systems and safeties”. This issue is still underexplored, making it difficult to see the extent of the problem and analyse where most data annotators are based. However, it does in some ways contradict the idea that most harms caused by AI are in the USA and UK as the google report concluded that ghost workers are often in geographies with limited labour laws, meaning AI is harming people elsewhere in different ways.

Post a comment